Sometimes historic buildings can take their time giving up their secrets. In such a case, it is well to have a flexible project design, one that takes account of the surprises and opportunities that renovation of an older building can furnish. An example is this 1840’s Gothic mansion on Beacon Hill, designed by Richard Upjohn, who designed the main entrances to the Boston Common. Originally a single 23,000 SF unit, in 1965 it was gutted and entirely stripped of its original finishes and trim in order to partition it into 15 modern residential units. As part of this work, the ceilings were dropped from a lofty 13 feet down to barely 7 feet.

Our project was to restore some of the original elegance and dignity to one of these units, on a fixed budget. Fortunately, our client was being advised by an interior design professional, who knew there would be issues that couldn’t be fully addressed at the beginning of the project. To begin, our project manager, Walter Mayne, furnished a budget and specifications for the work, room by room. Plans were only furnished as needed, as the work proceeded.

As we removed the 1965 finishes, we kept finding hints of what had been lost. When we cut an opening into a partition wall, we discovered several large original bolts, cut flush with the floor. Looking further, we understood that they had been part of a suspension rod system hanging from a wooden truss system above, holding up the floor. This caused us some concern, so we brought in a structural engineer. Further investigation revealed an old “mud” shadow on the wall indicating that that entire floor had originally been covered with slabs of marble, 2 inches thick, over ten tons total! With that weight gone, the floor structure was deemed more than adequate.

The saddest thing about the 1965 “renovation” was the loss of the high ceilings. The plan was to restore as much height as possible while furnishing chases and soffits necessary for modern systems and lighting. This requirement precluded simply exposing and restoring the old ceilings as the maximum final height would be short of 12 feet. Seeking guidance for our molding package, we went into the “loft” space, where we found plaster crown moldings spanning a full 24” vertical, ceiling plus wall. These we priced, in plaster, and it was not in the budget. As an alternative, we furnished the owner with three sample boards with crown package mockups sourced from Anderson McQuaid, a local wood molding manufacturer. One of these was selected, in poplar, for installation throughout the unit.

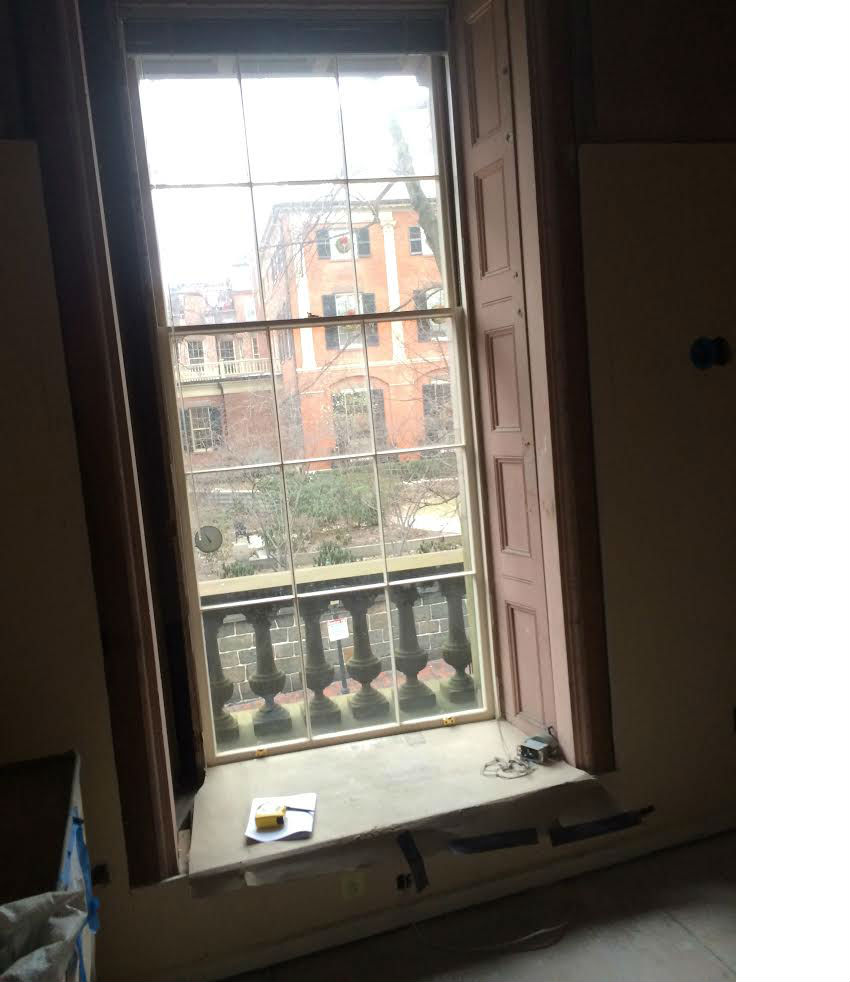

While still investigating the “loft” space, we were transiting an improvised “plank” across the 1965 ceiling joists and happened to notice that it was not a plank at all, but rather a shutter that happened to be just about the height of the newly exposed window openings. This had been part of an original bifold interior shutter system that retracted into still existing pockets in the deep window jambs. This happy discovery was used to fabricate a faithful reproduction for installation in one of the window cavities, fully functioning as the original once had.

What is gone is gone, but by remaining open to what the building had to tell us, we were able to recover much of the space’s original style, feeling, and purpose.